Reclaiming French Heritage at Fort St. Joseph in Niles, Michigan

par Nassaney, Michael S.

Fort St. Joseph was one of the most important eighteenth-century frontier outposts in the western Great Lakes region. Initially established by the French as a mission in the 1680s, the site became a hub of religious, military, and commercial activity for local Native American populations and European colonial powers for nearly a century. While late nineteenth-century collectors knew the location of the site, it became forgotten until its rediscovery in 1998 by Western Michigan University archaeologists. Subsequent investigations and public involvement have resurrected the community’s interest in its French heritage.

Article disponible en français : Patrimoine français du fort Saint-Joseph au Michigan

French Motivations for Exploration and Settlement in the Region

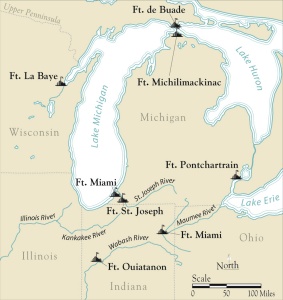

René-Robert Cavalier de La Salle visited the St. Joseph River valley in 1679 as the French sought to expand the fur trade and find a passage to the Far East. The following decade, the Jesuits were granted land by the French Crown for a mission along the river, near a strategic portage linking the St. Joseph River and the Great Lakes basin to the Mississippi drainage. In 1691 an outpost was established near the present-day southern boundary of Niles, Michigan. Governor General Frontenac authorized its construction in an attempt to solidify relations with the Miami and Potawatomi Indians in the immediate vicinity of the fort, strengthen ties with other tribes further west and north of the area, improve the fur trade in the region, and check the expansion and power of the Five Nations Iroquois Confederacy and their English allies. Although no detailed descriptions are known to exist, the post likely consisted of a palisade, a commandant’s house, and a few other structures.

Despite its religious origins, the French establishment on the St. Joseph River was known primarily for its commercial and military functions. It was a vital node in the colony's communications network and in the exchange of manufactured goods for furs obtained by the Natives. By the middle of the eighteenth century, it ranked fourth among all of New France's posts in terms of volume of furs traded. Fort St. Joseph played a prominent role in interactions between Native peoples and French and English colonial powers throughout the eighteenth century. Commanders who had served at Fort St. Joseph and Natives from the region were key players in events leading up to, and during, the Seven Years War that saw France lose Canada to the British. During Pontiac's Rebellion in the spring of 1763, supporters of the Ottawa leader attacked Fort St. Joseph in order to force the British from the area and encourage the return of the French.

The fort was not regarrisoned after Pontiac’s Rebellion and in 1781 a small group of French and Indians from the Illinois Country raided the fort. That expedition, which was supported by the Spanish governor at St. Louis, looted and occupied the fort for a day. The post was never reoccupied, although traders still frequented the valley into the early nineteenth century, when the area was part of America’s Northwest Territory.

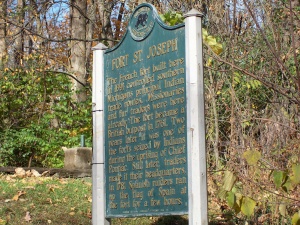

History Lost and Found

The site was in ruins when early pioneers settled the area in the 1830s. It soon became a popular collecting place, especially for the Miami Cross Society that amassed thousands of colonial artifacts from the vicinity of the site, including many French imports. In 1913 the St. Joseph Historical Society dedicated a 70-ton stone monument to commemorate the French efforts to civilize the wilderness, to use the language of the times. In 1918 the Women’s Progressive League of Niles erected a granite cross in honor of Father Allouez to replace a decaying wooden one. By the 1920s the City of Niles had adopted the moniker “City of Four Flags,” to distinguish it as the only place in Michigan that was once French, English, Spanish, and American territory. The placement of a nearby state historical marker in the 1950s legitimized the commemorative boulder, which represented the fort for generations of school children who visited the site. Meanwhile, landscape modifications beginning in the 1930s inundated part of the site beneath floodwaters and buried most of the remainder under 2 m of municipal waste, thwarting identification and excavation efforts.

Despite these challenges, some community members believed firmly that extant remnants could be located, investigated, and interpreted to the public. Support the Fort, Inc., a community organization devoted to the preservation and interpretation of the site, was formed in 1992 and invited WMU archaeologists to assist in locating the site. A survey was conducted in 1998 that led to the excavation and discovery of undisturbed artifact deposits and features that are providing information on architecture, daily life, and social relations. After more than a century, the once lost site of Fort St. Joseph had been found.

Community Archaeology at a Cultural Heritage Site: Public Education and Outreach

From the initial survey, the Fort St. Joseph Archaeological Project has been a collaborative endeavor. Local volunteers cleared brush, assisted in excavations, and provided meals for the archaeologists who, in turn, shared information about the discovery process and the significance of the remains for French colonial history. When archaeologists announced their discovery in 1998 and first opened their excavations to the public in 2000, scores of visitors demonstrated a genuine concern for the past and how archaeology is used to unravel clues about life in the eighteenth century.

Given the high level of community interest in archaeology, we have tried to create a dialogue to serve the needs of multiple constituencies who authorize and benefit from our work.

In 2007 the City Council appointed an official Archaeology Advisory Committee to formalize the partnership between the City of Niles and Western Michigan University (WMU). The committee consists of representatives from the City of Niles, WMU, the Fort St. Joseph Museum, and the local library, as well other preservationists, educators, community leaders, and interested parties. Recognizing the potential of the excavation to have significant implications for future heritage-related developments in the city, the members of the committee recommend the course of action for the investigation and promotion of the site and provide a valuable source of feedback on all aspects of the program. This partnership ensures that community education and involvement remain primary goals of the Fort St. Joseph Archaeological Project.

Our most intensive interaction with the community takes the form of our archaeology summer camps in which we teach the art, craft, and science of archaeology to middle/high school students, educators seeking continuing education credit, and life-long learners. More than 150 campers have taken part in the program since its inception. Many become staunch supporters of the project once they experience the thrill associated with the archaeological enterprise. Campers work under the supervision of undergraduate and graduate students who are enrolled in the University field school blurring the line between teaching and learning in a positive way.

The culmination of our field season is the annual open house. Begun in 2000, the open house was expanded in 2006 to attract an increasing number of visitors and provide multiple sensory experiences to the public. This collaborative weekend event is an opportunity for people of varying backgrounds and of all ages to witness ongoing archaeological excavations, interact with student archaeologists, see exhibits of recent artifact finds, learn about archaeology and eighteenth-century colonial life from informational panels, and enjoy period music, food, and demonstrations by professional historical re-enactors, all in their own backyard. Since 2006, over 10,000 people have experienced this free public event. Recent themes of the open house have included the “Jesuits in New France” (2009), “Women of New France” (2010), and “The Fur Trade” (2011). The militia will be the focus in 2012.

The living history component of the event includes professional re-enactors often representing French, British, and Native American men, women, and children who made up fur trader society on the edge of empire. The re-enactors insist on the historical accuracy of their clothing, accessories, and domestic items that they employ to show the public what life may have been like at the fort. Educational experiences are provided for children including mini-excavations and a “bead barter” that encourages children to ask the archaeologists and re-enactors various questions in exchange for beads.

An outdoor museum presents materials from our excavations and informational panels about the history of the fort, the process of site discovery, and the significance of our findings. This prepares the public to view the ongoing excavations and interact with student archaeologists who can hardly catch their breath when faced with literally hundreds of fascinated visitors. The tangibility of the past is so immediate when the public can observe artifacts as they are being recovered and learn about the way these artifacts are precisely recorded, processed for analysis, and interpreted. Viewing the excavations gives the local community a clear perception of where the fort was and where specific buildings may have been on the site. This makes the fort more than just an abstract City moniker but an actual place where people lived, worked, and played. As a result, visitors come away from the experience with a heightened sense of pride in local heritage and recognition of the French presence in the region. The thousands of attendees who visit the site each year confirm that people are curious about the history and archaeology of Fort St. Joseph and want to be actively engaged in reclaiming this French heritage.

The French Footprint in the Pays d’en Haut

Since 2002 archaeology has revealed five stone fireplaces representing domestic structures along the banks of the St. Joseph River. The recovery of numerous hand-wrought nails, bousillage (a mixture of clay and straw used to fill in the spaces between the upright posts in French buildings), pierrotage (a mixture of stones and mortar), and hardware such as hinges testify to European-style building techniques. Numerous artifacts have been found in association with these architectural remains and elsewhere on the site. These artifacts and their spatial relationships are providing information on activity areas, particularly in regards to production and exchange. For example, a broad range of artifact types are represented, reflecting the religious, military, and commercial functions of the site including crucifixes, religious medallions, military buttons, gun parts, domestic objects (ceramics, glass containers), objects of personal adornment (cuff links, finger rings), glass beads, lead seals used to identify bolts of cloth, and baling needles to wrap bundles of furs [Illustration 9]. One area of the site yielded a concentration of over 100 gun parts that has been interpreted as a gunsmith’s repair kit. Documentary sources indicate that the French repaired Native guns as a service. Adjacent to one of the fireplaces were numerous glass beads, several straight pins, and an awl, suggesting leather working and embroidering in the fire’s light and heat. Other areas have yielded evidence for the production of musket balls or lead shot as indicated by molten lead and sprue. Numerous scraps of copper alloy derive from cutting sheet metal to produce patches and rivets to repair worn out kettles and tinkling cones—cone-shaped ornaments used to decorate clothing or leather bags. Both burned and unburned bones have also been found, pointing to cooking and discard locations. Some Native-style artifacts such as stone smoking pipes, bone tools, antler gaming pieces, and stone and metal projectile points have also been recovered from excavations at the fort indicating the multiethnic background of the occupants.

Dietary remains consist of copious amounts of well-preserved animal bones, particularly from deer, beaver, raccoon, bear, and turkey. Relatively small amounts of domesticated animals (swine, cattle, horse, and chicken) have been found. Indian corn dominates the assemblage of plant remains, though only a limited amount of flotation has been conducted. Flotation is a technique whereby soil from an archaeological site is placed in water to collect organic materials that float to the surface. Most of the corn consists of carbonized cobs that were found in a small pit feature that has been interpreted as a smudge pit used to tan hides.

Ultimately, the goals of archaeology at Fort St. Joseph are to gain a better understanding of the demographic composition of the fort and the identities of its occupants. Lists of commanders and soldiers reveal a military presence at the fort as well as an interpreter to assist in dealings with Natives. In the early 1720s the garrison consisted of 10 soldiers and 8 officers and by 1750 the fort supported about 20 families. Records document the presence of French and Native women, some of the latter married to French men, along with Indian slaves and servants; a master carpenter; and a blacksmith who could repair guns.

In sum, archaeology is beginning to reveal the activities, and by inference, the identities of some of the fort occupants. The presence of certain artifacts and practices such as stone smoking pipes, antler gaming pieces, wild animal food remains, and smudge pits suggest that the French had fully incorporated Native peoples into daily activities at the fort and began to adopt Native practices, thus creating a new cultural identity on the frontier.

The Future of the Past at Fort St. Joseph

The process of investigating and interpreting the history of Fort St. Joseph is in constant flux as new students, faculty, volunteers, and advisory committee members become involved. In 2008 the City of Niles and WMU signed a 10-year collaborative agreement to ensure future study of the site. A summer archaeology lecture series was initiated in 2009 to provide professional presentations on topics of related interest to the public. The informational panels from the open house are posted to our web site (http://www.wmich.edu/fortstjoseph/) and three documentary DVDs have been produced and distributed to area schools, teachers, and the public. The videos explore the research design, students’ community service learning experiences, and stakeholders’ responses to public education and outreach activities. In 2011 we began publication of the Fort St. Joseph Archaeological Project Booklet Series intended for a general audience and distributed free of charge. The first issue was sponsored by the Michigan Humanities Council (MHC) and focused on the women of New France. The second issue (2012), also sponsored by the MHC, highlights the role of the fur trade in intercultural encounters in New France and elsewhere in North America.

Documentary and archaeological evidence collected thus far suggests that Fort St. Joseph was a multiethnic community in which the French and Native peoples were mutually dependent and freely shared information and ideas as they intermarried and created alliances along the frontier in the western Great Lakes. As the people of Niles reclaim this heritage, they will become aware of the future possibilities for living in a culturally diverse society that is inspired by the lessons they learn from their French predecessors.

Michael S. Nassaney

Professor of Anthropology

Western Michigan

University

Bibliography

Beeson, L. H. «Fort St. Joseph—The Mission, Trading Post and Fort, Located about One Mile South of Niles, Michigan», Collections of the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society, no. 28, 1900, pp. 179-86.

Brandão, José António, and Michael S. Nassaney, «A Capsule Social and Material History of Fort St. Joseph (1691-1763) and Its Inhabitants», French Colonial History vol. 7, 2006, pp. 61-75.

Coolidge, Orville W., «Address at the Dedication of the Boulder Marking the Site of Fort St. Joseph. Collections of the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society», vol. 39, 1915, pp. 283-291.

Hulse, Charles A., «An Archaeological Evaluation of Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), Berrien County, Michigan», The Michigan Archaeologist vol. 27, nos. 3-4, 1981, pp. 55-76.

Nassaney, Michael S., «Identity Formation at a French Colonial Outpost in the North American Interior», International Journal of Historical Archaeology vol. 12, no. 4, 2008, pp. 297-318.

Nassaney, Michael S., «Public Involvement in the Fort St. Joseph Archaeological Project», Present Pasts vol. 3, 2011, pp. 42-51 DOI: 10.5334/pp.43.

Nassaney, Michael S., editor, An Archaeological Reconnaissance Survey to Locate Remains of Fort St. Joseph (20BE23), in Niles, Michigan. Archaeological Report No. 22. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Department of Anthropology, Western Michigan University, 136 pp.

Nassaney, Michael S., José António Brandão, William Cremin, and Brock A. Giordano, «Archaeological Evidence of Daily Life at an 18th-Century Outpost in the Western Great Lakes», Historical Archaeology vol. 41, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-17.

Nassaney, Michael S., William Cremin, Renee Kurtzweil, and José António Brandão, «The Search for Fort St. Joseph (1691-1781) in Niles, Michigan», Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology vol. 28, no. 2, 2003, pp. 1-38.

Peyser, Joseph L., editor, Letters from New France: the Upper Country, 1686-1783. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992, 248 p.

Peyser, Joseph L. and Robert C. Myers, Fort St. Joseph, 1691-1781: The Story of Berrien County’s Colonial Past, Berrien Springs, MI, The Berrien County Historical Association, 1991, 35 p.

Quimby, George I., Indian Culture and European Trade Goods. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1966, 117 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

«Fort St Joseph, 1691

«Fort St Joseph, 1691

-1781» -

Map of southwest Mich

Map of southwest Mich

igan and adjoin... -

This early twentieth

This early twentieth

century postcar... -

The granite cross, de

The granite cross, de

dicated to Fath...

-

A brass kettle from t

A brass kettle from t

he vicinity of ... -

Fort St.Joseph Museum

Fort St.Joseph Museum

entrance, Octo... -

Fort St.Joseph – Outd

Fort St.Joseph – Outd

oor Museum incl... -

Fort St.Joseph – The

Fort St.Joseph – The

fort site durin...

-

Fort St.Joseph – Medi

Fort St.Joseph – Medi

a day speeches:... -

Fort St.Joseph – Cuff

Fort St.Joseph – Cuff

link with green... -

Fort St. Joseph – Tin

Fort St. Joseph – Tin

kling cones wer... -

Fort St.Joseph – Illu

Fort St.Joseph – Illu

stration of lea...

-

Fort St.Joseph – Clea

Fort St.Joseph – Clea

r glass inset -

Fort St.Joseph – WMU

Fort St.Joseph – WMU

student excavat... -

Fort St.Joseph – WMU

Fort St.Joseph – WMU

student interac... -

Fort St.Joseph – WMU

Fort St.Joseph – WMU

students wet sc...

-

Fort St.Joseph – Stud

Fort St.Joseph – Stud

ents excavating... -

Fort St.Joseph – Cera

Fort St.Joseph – Cera

mic fragment in... -

Fort St.Joseph – Mout

Fort St.Joseph – Mout

h harp -

Fort St.Joseph – The

Fort St.Joseph – The

public listenin...

-

Fort St.Joseph – Axe

Fort St.Joseph – Axe

head from metal... -

Fort St.Joseph – Ribb

Fort St.Joseph – Ribb

on cutting on m... -

Fort St.Joseph – The

Fort St.Joseph – The

fort site durin... -

Fort St.Joseph – Jesu

Fort St.Joseph – Jesu

it priest overl...

-

Fort St.Joseph – Copp

Fort St.Joseph – Copp

er alloy adornm... -

Fort St.Joseph – Ramr

Fort St.Joseph – Ramr

od guide -

Fort St.Joseph – Iron

Fort St.Joseph – Iron

awl -

Fort St.Joseph – Meta

Fort St.Joseph – Meta

l cache (includ...

-

Fort St.Joseph – Lead

Fort St.Joseph – Lead

seal reading “... -

Fort St.Joseph – Wet

Fort St.Joseph – Wet

Screen Setup: u... -

Fort St.Joseph – Visi

Fort St.Joseph – Visi

tors interactin... -

Fort St.Joseph – Voya

Fort St.Joseph – Voya

geurs unloading...

-

Fort St.Joseph – view

Fort St.Joseph – view

of site -

Summer campers partic

Summer campers partic

ipate in archae... -

Michigan Historic Sit

Michigan Historic Sit

e: Fort St.Jose... -

The Michigan State Hi

The Michigan State Hi

storical Marker...